The Bugbear of Training: How to Avoid

by Arthur Saxon

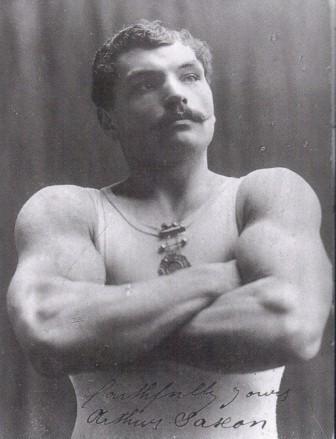

Arthur Saxon, on the cover of his book The Development of Physical Power, which was originally published in 1906.

I take it for granted that no one can enter into training for any sport, including weightlifting, and even practice for physical development only, without encountering monotony in training, which threatens to upset all schemes for daily exercise, throwing one back in one’s work, especially as staleness makes its appearance. I, of course, am more directly concerned with weightlifting exercises than with any other, but, no doubt, when I have given my views as to how one may steadily progress, and at all times make some little advance, however slight, and overcome the bugbear of training, then it will be found possible to adapt my hints to other forms of exercise.

In the first place, when you feel a little stale, yet, perhaps, not stale enough to make a total rest advisable, then, when you lift, if you lift all weights, whether in practicing feats or weightlifting exercises, at such a poundage that they can be readily raised with ease and comfort, it will be found that your work is once more a pleasure, and short you may return to your usual poundage. The bugbear or training loses half its fearsome aspect to the tired athletes who has a lot at stake, and must continue at his work, if it be done in company with a friend or friends. There is nothing so fatiguing as the raising of iron weights time after time with no one to watch, no one to encourage, no one to advise – to express surprise at your improvement. To surprise and beat your friends is always an encouragement, and in practicing with weights you cannot get the right positions unless you have an expert lifter to occasionally offer a hint. Lifting, too, may become dangerous if practiced by oneself, so you see the idea is to endeavor to make your training as much as pleasure as possible. If necessary, enter into little competitions with your friends. I had almost said a small bet would be an incentive to work, but I suppose I must include betting among the list of vices we human beings are apt to give way to, but this will not preclude one from a friendly competition occasionally in which points may be conceded, and lifts performed on handicap and competition lines.

Carefully adjust your work to your condition at the moment. Ask yourself each time you lift, “Am I in good form today?” If you feel yourself in good form – specially “fit” – then that is the time to try a “limit” lift. Note what you have raised that day – the weight and the date – and at another suitable time see if you can surpass your last record lift by a few points.

Such pleasant, invigorating and helpful aids to training as massage, towel friction and sponge-down, are all direct helps in aiding one to continue constantly and persistently with the practice. Without regularity good results cannot be expected, yet immediately your mind, always questioning your condition, and ever ready to appreciate a weakness, tells you that you are stale, an immediate and entire rest is imperative. To go on when stale is to invite an entire breakdown. I have known even nervous exhaustion to attend the misdirected efforts of the athlete who persists in hard training when he feels himself going to pieces through over-work. To try to work like a machine, knowing that ever at one’s side stands the bugbear of training, ready to weaken one’s resources through over-work, and bring about a breakdown, is the height of folly. Nature has given one an instinct which will make heard, with warning notes, the danger signal when over fatigue threatens, and this signal should never be allowed to pass unnoticed.

Whilst on this subject, I would point out that the man of sedentary occupation can never hope to stand the same amount of physical work as regards to weightlifting as his fellow, who is a manual laborer, and whose muscles are daily tuned to mechanical labor, which drains the system least of any, whilst brain work is a constant and steady drain on the whole system, and it will, no doubt, surprise many to learn that the brain-worker is more likely to suffer from over-work than the man who, like myself, daily performs arduous feats which are purely muscular. When the brain-worker changes to physical work, he finds the change helpful, inasmuch as a change of work is a good as a rest, and, therefore, he will not, of course, regard the lifts he practices as work, but as a pleasant pastime.

Credit: The Development of Physical Power by Arthur Saxon